Abstract

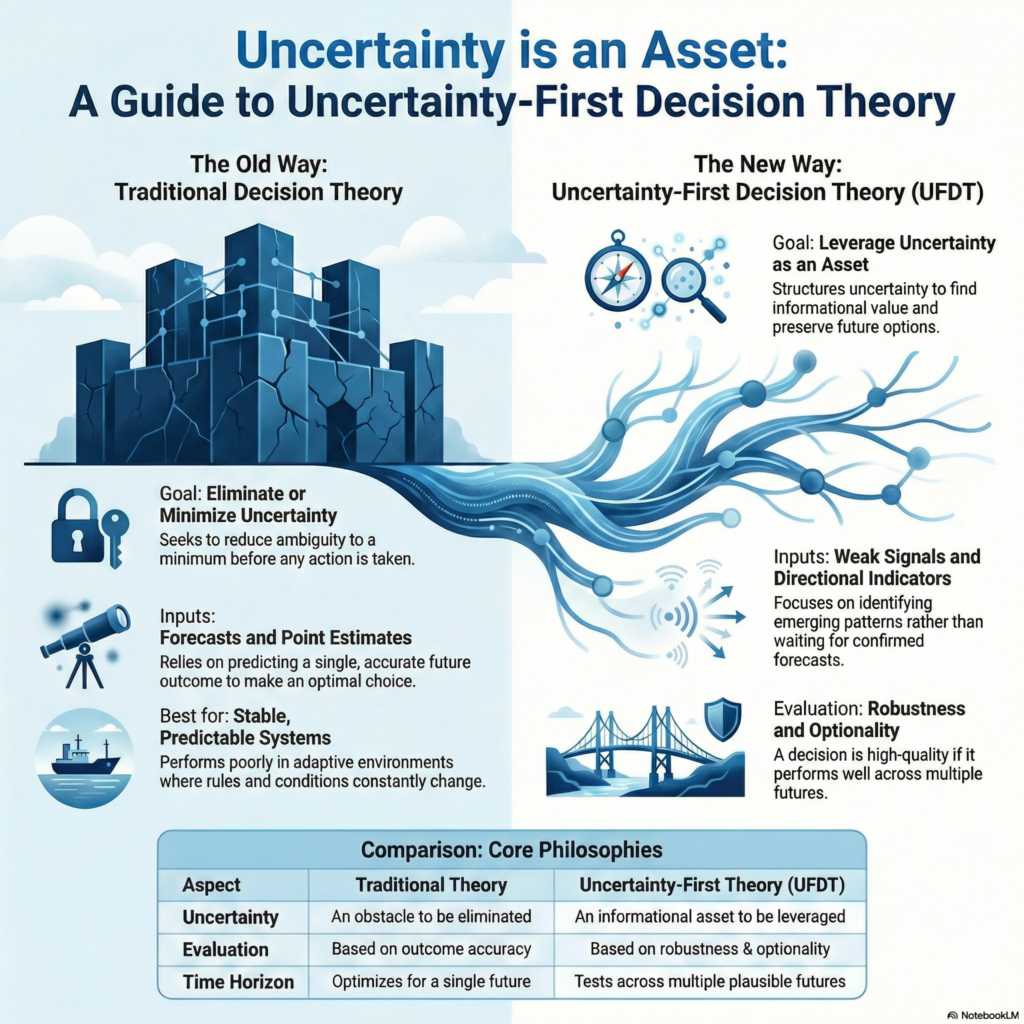

Classical decision theory prioritizes optimization under known probabilities or seeks to reduce uncertainty to a minimum before action.

This paper proposes an alternative approach: Uncertainty‑First Decision Theory (UFDT). UFDT treats uncertainty not as a defect to be eliminated, but as a primary source of informational value.

We formalize uncertainty as a measurable and actionable condition, introduce a signal‑based decision model, and demonstrate how decisions can be evaluated based on robustness, optionality, and surprise reduction rather than outcome accuracy alone.

This framework is intended for environments characterized by complexity, nonlinearity, and rapid change.

Learning Objectives

By reading this article, you will:

- Understand the limitations of traditional decision frameworks in uncertain environments

- Learn the core principles of Uncertainty‑First Decision Theory (UFDT) and how it differs from classical approaches

- Discover how to evaluate signals and make decisions under uncertainty using the five-dimensional signal evaluation model

- Identify when UFDT is most applicable to your decision-making context

- Recognize how to structure uncertainty as an informational asset rather than an obstacle

Time Investment: 15-20 minutes

Prerequisites: Basic familiarity with decision-making concepts is helpful but not required

Expected Outcome: Clear understanding of UFDT principles and practical application framework

Before you start, listen to a brief summary: Hunt for Signals in the Ambiguous Zone

1. Introduction

Decision‑making in real‑world systems rarely occurs under conditions of certainty. Economic markets, technological change, geopolitical dynamics, climate systems, and human behavior all exhibit nonlinear feedback, incomplete information, and emergent properties.

Traditional models often assume that uncertainty can be reduced to stable probabilities or that optimal decisions converge with sufficient data. Empirical evidence suggests otherwise: many systemic failures arise not from insufficient data, but from misinterpreting or ignoring uncertainty itself.

This paper advances the thesis that uncertainty is not merely unavoidable but instrumental to intelligent decision‑making.

For practical applications of these principles, see our guide on Decision Intelligence, Explained, which demonstrates how these theoretical frameworks are applied in practice.

2. Limitations of Traditional Decision Frameworks

Classical approaches—including expected utility theory, rational choice theory, and single‑forecast optimization—exhibit several failure modes in uncertain environments:

- Overconfidence derived from point estimates

- Fragility to regime shifts

- Delayed response due to demand for confirmation

- Narrative lock‑in and hindsight bias

These approaches tend to perform well in stable, repeatable systems and poorly in adaptive, evolving ones.

UFDT vs. Traditional Decision Theory

| Aspect | Traditional Decision Theory | Uncertainty-First Decision Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Treatment | Seeks to minimize or eliminate | Optimizes for a single future |

| Decision Inputs | Forecasts and point estimates | Signals and directional indicators |

| Evaluation Criteria | Outcome accuracy | Robustness, optionality, surprise reduction |

| Time Horizon | Optimizes for single future | Tests across multiple plausible futures |

| Belief Updating | Symmetric confidence changes | Asymmetric (slow increase, rapid decrease) |

| Best For | Stable, repeatable systems | Complex, adaptive, rapidly changing systems |

3. Defining Uncertainty

3.1 Formal Definition

Uncertainty is defined as the divergence between the observer’s information state and the true system state, including:

- Incomplete or delayed information

- Unknown causal relationships

- Stochastic variation

- Emergent behaviors are not inferable from components

Uncertainty is therefore epistemic (knowledge‑based) and structural (system‑based).

3.2 Distinction from Risk

Risk assumes known probability distributions. Uncertainty includes situations in which the probabilities themselves are unstable or unknowable.

4. Core Principle of Uncertainty‑First Decision Theory

The informational value of a decision increases as certainty decreases, provided uncertainty is structured rather than ignored.

Decisions made under high certainty tend to reflect consensus and offer limited strategic advantage. Decisions made under structured uncertainty preserve optionality and enable early positioning.

5. The Uncertainty Gradient

We model future states along an uncertainty gradient:

| Zone | Characteristics | Signal Strength | Strategic Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certainty Zone | Outcomes largely agreed upon | Strong, confirmed | Limited (consensus already priced in) |

| Probabilistic Zone | Competing likelihoods | Moderate, measurable | Moderate (requires probability assessment) |

| Ambiguous Zone | Weak signals and partial patterns | Weak, emerging | High (early positioning possible) |

| Unknown Zone | Absence of observable signals | None | None (no actionable information) |

Empirical advantage is concentrated in the Ambiguous Zone, where early signals precede confirmation. This is where decision intelligence frameworks like Prediction Oracle’s approach provide the most value.

6. Signal‑Based Decision Inputs

Rather than relying on forecasts, UFDT operates on signals, defined as deviations from baseline system behavior. Each signal is evaluated across five dimensions:

6.1 Signal Evaluation Dimensions

| Dimension | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Novelty | How new or unexpected is this signal? | First-mover in emerging technology category |

| Momentum | Is the signal accelerating or decelerating? | Increasing adoption rate over time |

| Cross‑Domain Resonance | Does this signal appear in multiple unrelated domains? | Same pattern in tech, finance, and policy |

| Credibility | What is the quality and reliability of the signal source? | Verified data from authoritative sources |

| Optionality Impact | How does this signal affect future decision flexibility? | Opens new options while preserving existing ones |

Signals are not predictions; they are directional indicators. This approach aligns with weak-signal first thinking in decision intelligence frameworks.

7. Decision Evaluation Criteria

UFDT rejects outcome‑only evaluation. Decision quality is assessed by:

- Explicit acknowledgment of uncertainty

- Preservation of optionality

- Robustness across plausible futures

- Capacity for rapid belief updating

- Reduction of surprise magnitude

A decision may be considered high‑quality even if the realized outcome is unfavorable.

8. Scenario‑Relative Reasoning

UFDT replaces single‑path forecasting with scenario‑relative evaluation. Decisions are tested against multiple plausible futures, and preference is given to actions that fail gracefully rather than catastrophically.

9. Belief Updating and Adaptation

Beliefs are treated as provisional and asymmetrically updated:

- Confidence increases slowly

- Confidence decreases rapidly when contradicted

This asymmetry reduces overconfidence and accelerates adaptation during regime shifts.

10. Failure Modes Avoided

Uncertainty‑First systems demonstrate resilience against:

- Overconfidence collapse

- Late‑stage reaction

- Narrative fixation

- Structural fragility

11. Practical Application

UFDT is applicable to domains including:

- Strategic planning — Navigating market shifts and competitive dynamics

- Financial allocation — Portfolio decisions under market uncertainty

- Technology adoption — Evaluating emerging technologies before consensus forms

- Career and human capital decisions — Skill development and career pivots

- Institutional risk management — Preparing for multiple plausible futures

The framework emphasizes early positioning, incremental commitment, and continuous reassessment.

Real-World Example: Technology Adoption

Consider a company evaluating whether to adopt a new AI capability. Traditional decision-making might wait for:

- Clear ROI projections

- Industry consensus

- Regulatory clarity

UFDT would instead:

- Monitor weak signals (early adopter feedback, research trends, regulatory discussions)

- Take a small, reversible position (pilot program with 1-2% resource allocation)

- Set clear triggers for scaling or exiting

- Treat learning as a primary return

This approach is demonstrated in our Decision Checklist, which provides a practical framework for applying UFDT principles.

12. Conclusion

Uncertainty‑First Decision Theory reframes uncertainty as an informational asset rather than an obstacle. By structuring uncertainty through signals, scenarios, and adaptive evaluation, decision‑makers can act earlier, preserve flexibility, and reduce systemic surprise.

In complex and rapidly evolving environments, intelligence is best measured not by prediction accuracy but by adaptability.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does UFDT differ from traditional decision theory?

Traditional decision theory seeks to minimize uncertainty and optimize for known probabilities. UFDT treats uncertainty as a source of informational value, structures it through signals and scenarios, and evaluates decisions based on robustness and optionality rather than outcome accuracy alone.

When should I use Uncertainty-First Decision Theory?

UFDT is most valuable when:

- Operating in complex, rapidly changing environments

- Facing incomplete information and weak signals

- Making long-horizon or high-stakes decisions

- Traditional optimization approaches have failed

- Early positioning provides a strategic advantage

What are the key differences between risk and uncertainty?

Risk assumes known probability distributions (e.g., “30% chance of market downturn”). Uncertainty includes conditions where probabilities themselves are unstable or unknowable (e.g., “unknown likelihood of regulatory changes”). UFDT is designed for uncertainty, not risk.

How do I evaluate signals using the five dimensions?

Evaluate each signal across:

- Novelty — Is this new or unexpected?

- Momentum — Is it accelerating or decelerating?

- Cross-Domain Resonance — Does it appear in multiple domains?

- Credibility — What is the quality of the source?

- Optionality Impact — How does it affect future flexibility?

Signals with high scores across multiple dimensions warrant closer attention.

Can UFDT be applied to personal decisions?

Yes. UFDT principles apply to any decision under uncertainty, including:

- Career changes and skill development

- Investment decisions

- Relationship and life choices

- Educational paths

The key is structuring uncertainty, taking small reversible positions, and setting clear triggers for adaptation.

How does UFDT relate to decision intelligence?

UFDT provides the theoretical foundation for decision intelligence frameworks. Decision Intelligence applies UFDT principles through practical tools like weak-signal detection, explicit uncertainty management, and multiple reasoning lenses.

What is the “Ambiguous Zone” and why is it important?

The Ambiguous Zone is where weak signals and partial patterns exist before confirmation. This is where empirical advantage is concentrated because early positioning is still possible. Once signals move to the Certainty Zone, consensus has formed and strategic advantage is limited.

How do I implement UFDT in my organization?

Start with:

- Identifying decisions made under uncertainty

- Establishing signal monitoring systems

- Taking small, reversible positions (1-2% allocation)

- Setting pre-committed triggers for scaling or exiting

- Treating learning as a primary return

See our Decision Checklist for a practical implementation framework.

Does UFDT require special tools or software?

While tools like Prediction Oracle’s Decision Intelligence Documents can help, UFDT principles can be applied with any system that helps you:

- Monitor weak signals

- Structure uncertainty explicitly

- Test decisions across multiple scenarios

- Set clear adaptation triggers

How does belief updating work in UFDT?

Beliefs are updated asymmetrically:

- Confidence increases slowly — requiring multiple confirmations

- Confidence decreases rapidly — when contradicted by evidence

This asymmetry reduces overconfidence and accelerates adaptation during regime shifts.

Next Steps

Ready to apply Uncertainty-First Decision Theory to your decisions?

Explore Decision Intelligence in Practice

See how UFDT principles are applied in real-world scenarios through our Decision Intelligence Documents, which demonstrate signal-based evaluation, explicit uncertainty management, and scenario-relative reasoning.

Learn How to Read Decision Intelligence Documents

Understand how to extract maximum value from Decision Intelligence Documents with our practical guide: How to Read Decision Intelligence Documents.

Use the Decision Checklist

Put UFDT into practice with our Decision Checklist, which provides a step-by-step framework for making decisions under uncertainty using staged entry, pre-committed triggers, and optionality preservation.

Understand Uncertainty Management

Deepen your understanding of how to work with uncertainty in our Uncertainty Summary for Emerging AI Trends 2026, which shows how uncertainty is explicitly structured and managed.

Additional Resources

- Decision Intelligence, Explained — Practical framework based on UFDT principles

- Robust Decision-Making — RAND Corporation research on decision-making under deep uncertainty

- Decision Theory — Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Academic foundations

References

- Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Taleb, N. N. (2010). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Random House.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Rationality for Mortals: How People Cope with Uncertainty. Oxford University Press.